Numerous science fiction films – from Star Trek to 2001: A Space Odyssey to Blade Runner – are populated by classic designs that have shaped our image of the future. In reverse, many designers of objects destined for some type of imagined future seek inspiration in the genre of science fiction. The fascinating dialogue between science fiction and design is the subject of a new exhibition in the Vitra Schaudepot. Under the title "Science Fiction Design: From Space Age to Metaverse", over 100 objects from the museum’s collection will be staged in a futuristic display by the Argentine visual artist and designer Andrés Reisinger. Supplemented by selected works from the realms of film and literature, the show presents a range of examples from the early twentieth century to the so-called Space Age of the 1960s and ’70s, and even further to recent design objects that have been conceived exclusively for the virtual worlds of the metaverse.

The literary genre of science fiction first became popular in the nineteenth century, when the sudden rise of technology during the Industrial Age inspired authors such as Mary Shelley and Jules Verne to imagine how the era’s urgent issues would play out in a future fictional world. From the outset, the genre focused on the central questions of humankind – touching on love, war and death in the context of time and space travel, or under the risks and opportunities of new technologies. With the advent of moving pictures, science fiction was soon adopted as a major cinematic theme. This is demonstrated in the exhibition by one of the seminal early works in the history of film: in A Trip to the Moon from the year 1902, the French director Georges Meliès envisioned the flight of a rocket to the moon, resulting in the archetypical science fiction movie. Over the following decades, science fiction not only experienced a quick ascent in the film industry, but also generated new forms in the literary and graphic arts, such as comics and pulp magazines that reached a global fan base with garish covers and stories penned by renowned authors like Isaac Asimov, Stanislaw Lem and H.G. Wells.

What was first anticipated by science fiction started to become a reality in the 1950s: the first satellites were shot into space, aerospace technology experienced rapid advancement, and the two Cold War superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, engaged in a moon race that captivated the entire world like a suspense novel. The Space Age also found manifold expression in the realm of design.

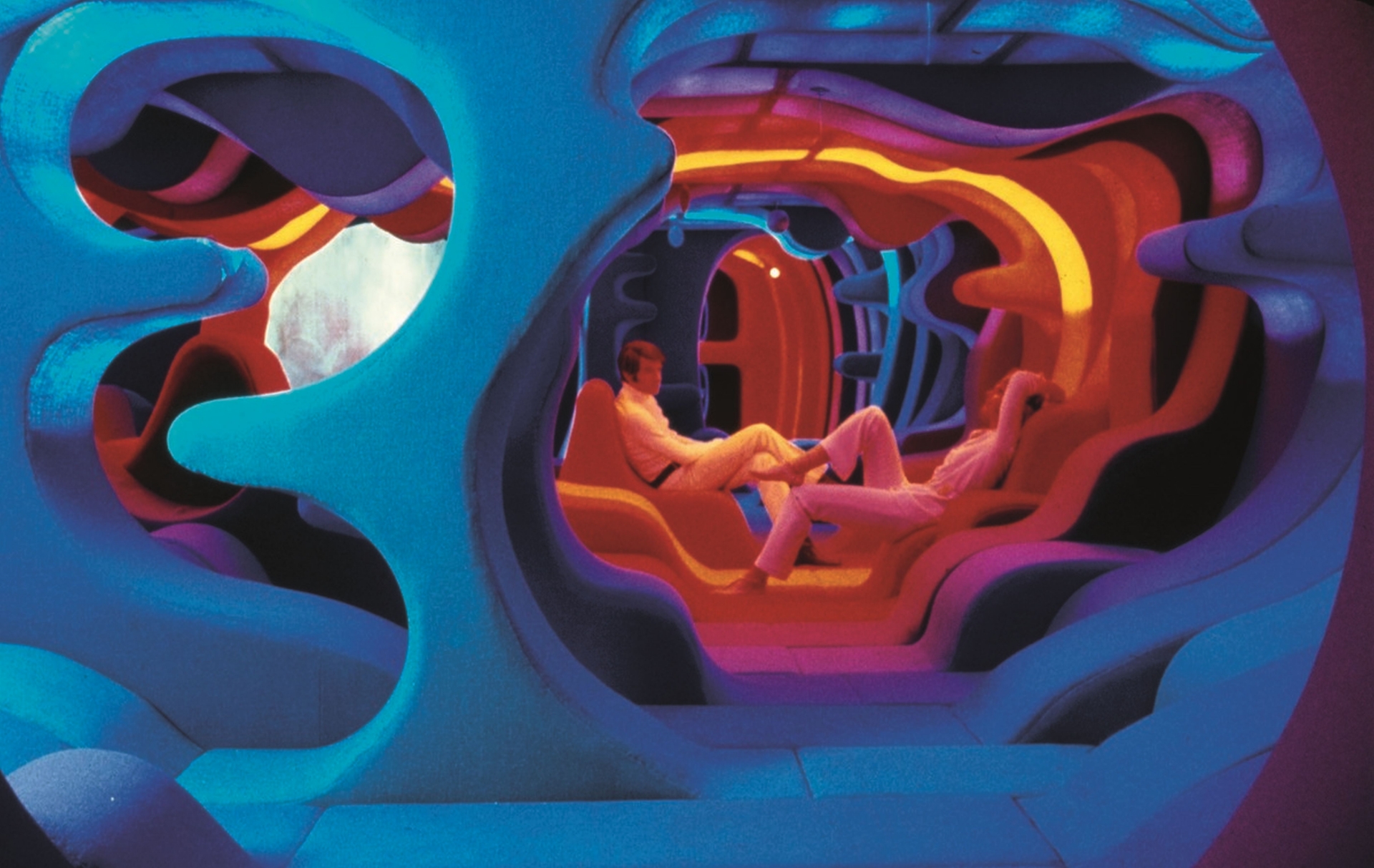

Designers such as Gae Aulenti, Eero Aarnio, Luigi Colani, Joe Colombo and Verner Panton created furnishings and living environments whose organic shapes and shiny plastic surfaces not only looked futuristic, but also reflected a fundamental rethinking of modern lifestyles. Finding inspiration in the technology of space travel, the designers of the Space Age supplied film directors with the ideal furnishings for their science fiction movies. Designer furniture surged on the silver screen: Olivier Mourgue’s Djinn seating series in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); Eero Aarnio’s Tomato Chair in Barry Sonnenfeld’s Men in Black (1997); Pierre Paulin’s Ribbon Chair in Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 (2017), to name a few.

The dialogue between science fiction and design persisted into the following decades. Iconic designs continued to appear in science fiction films, such as Marc Newson’s Orgone Chair in Prometheus (2012) – along with unexpected examples like Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Argyle Chair (1897) in Blade Runner (1982). In this respect, science fiction has proven to be a multifaceted genre that also addresses controversial topics such as climate change and artificial intelligence. The new possibilities enabled by computer-aided design and 3D printing have contributed to the revival of a futuristic aesthetic, from which new classics have emerged, such as Joris Laarman’s Aluminum Gradient Chair (2013), the first 3D-printed metal chair. In light of the current space exploration efforts, there is talk of a Second Space Age. This raises questions about how the dialogue between science fiction and design is progressing today, and what it might look like in the future. Applying innovative technologies to pressing social problems and challenges is just one conceivable scenario. The other is the metaverse, which, for a new generation of young designers, appears to be evolving into what the cosmos represented in the 1960s – a new space for projections and experiments, a place for free thinking that can be filled with novel ideas and concepts.

As an example of this approach, the exhibition also features works by Andrés Reisinger, currently one of the most prominent figures creating and designing for both the physical realm and the metaverse. Reisinger’s digital artworks, often featuring furniture, are marketed as NFTs and attain high attention. His perfectly staged dreamscapes give expression to the aesthetic preferences and sensibilities of a digital generation, while clearly referencing the imagery of earlier science fiction films. On display in the show are Reisinger’s Shipping Series (2021) and his Hortensia Chair (2018), the latter a playful and simultaneously futuristic object that the artist and designer initially developed as an NFT before producing it as an actual piece of furniture. The creative direction of the exhibition has also been entrusted to Andrés Reisinger, who shares: “As soon as I was invited by the Vitra Design Museum to work on this exhibition, I knew I wanted to incorporate the themes of Argentine fantasy writer Jorge Luis Borges, whom I’ve long admired. A central motif in his work is mirrors, symbolic of portals to alternate realities. With this in mind, I resolved to honor Borges by making mirrors focal points of the exhibition, utilizing them to reflect and evoke multiple realities and timelines intertwining, creating a new dimension within our contemporary world. I am thrilled with what we have achieved with this exhibition, which speaks of a time and a space that truly knows no time and space.”