A relentlessly innovative and subversive sculptor, Tom Sachs is best known for his elaborate bricolage recreations of masterpieces of engineering and design. Humble foam core and plywood replace the gleaming aluminium and polycarbonate of mass-produced items, fabricated with the combination of industrial vigour and handmade artistry that have become his trademark. The themes central to his universe focus on American culture and society, which he treats with a heavy dose of humour and irony. He playfully engages with the corporate ecosystem and the idea of ‘brand image’ by riffing on luxury consumer items and global brands, which are transformed through their inclusion in an art context.

In the 1990s, Sachs spent days studying Piet Mondrian’s paintings at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, using duct tape on plywood to recreate several of them. It was through these early explorations that he began to develop the ethos of his studio, reconstructing objects he desired with the materials that were available to him and intentionally revealing his process, with all its challenges and imperfections. His works are conspicuously handmade and heighten our awareness of production techniques, in a reversal of modernisation’s trend towards cleaner, simpler and more perfect machine-made items. From his meticulously crafted sculptures and vibrant paintings to his pioneering work in Web3 and NFTs, as well as his boundary-pushing designs and collaborations, Sachs continues to inspire and challenge conventional artistic practices.

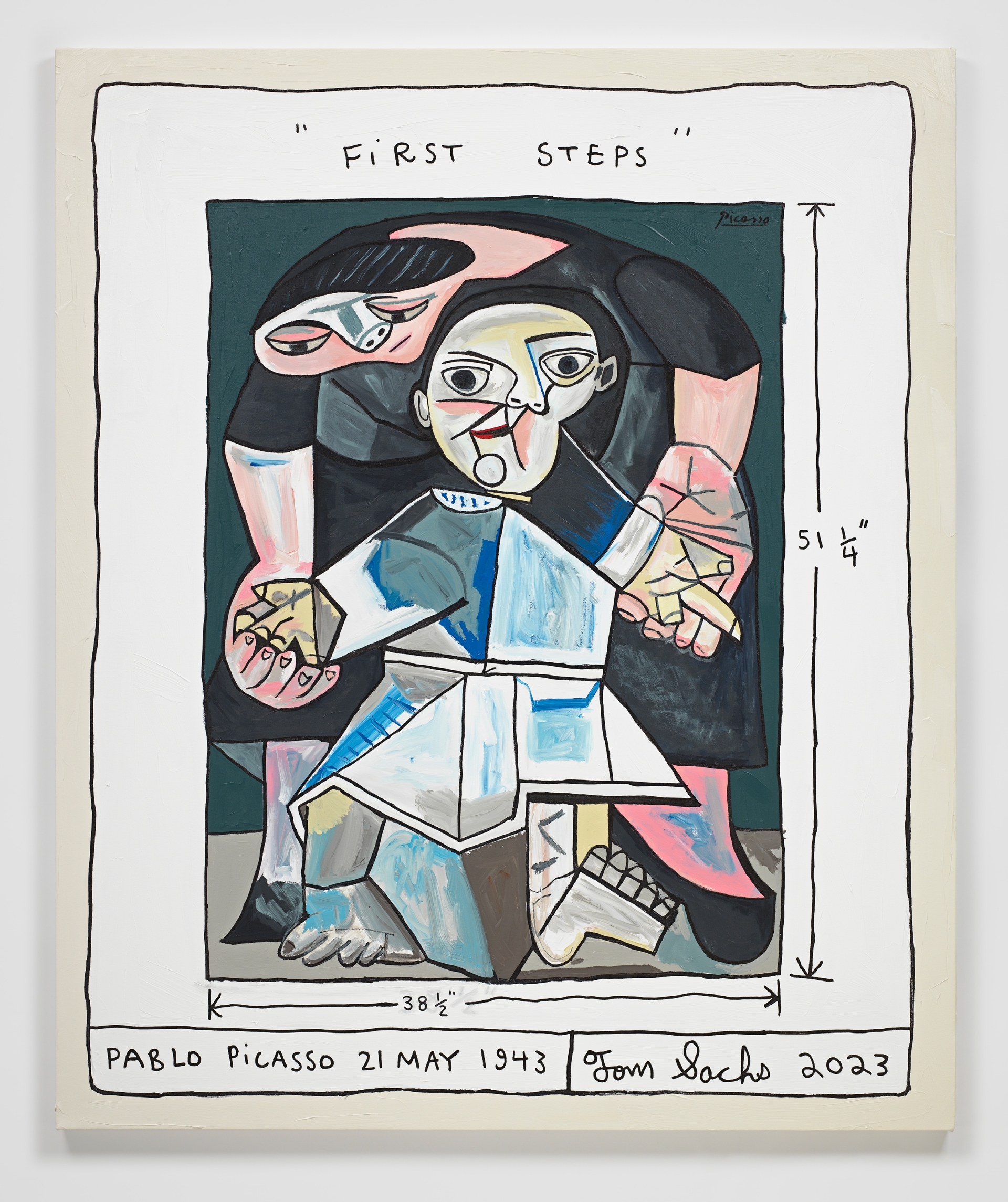

First Steps, 2023

Acrylic and Krink on canvas

182,9 x 152,4 x 3,8 cm (72 x 60 x 1,5 in)

(TSA 1464)

Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul © Tom Sachs. Photos: Studio Tom Sachs

Sachs was born in 1966 in New York, where he lives and works. His work has been exhibited across the world and is held in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris; The Met- ropolitan Museum of Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and Prada Foundation, Milan, among others. He has had major solo exhibitions at Deichtorhallen, Hamburg (2021); Tokyo City Opera (2019); Nasher Sculpture Center, Houston (2017); Noguchi Museum, New York (2016); Yerba Buena Arts Center, San Francisco (2016); Brooklyn Museum, New York (2016); Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2016); Lyon Biennale, France (2013); Park Avenue Armory, New York (2012); Venetian Architecture Biennale (2010); Prada Foundation, Milan (2006); and Guggenheim Museum, Berlin (2003).

For this exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac Paris Marais, artist Tom Sachs has immersed himself in paintings Pablo Picasso produced during his so-called ‘War Years’, between 1937 and 1945. Reimagining Picasso’s work using his own distinctive painterly language, Sachs also challenges Picasso by contrasting him with two opponents: longstanding rival Marcel Duchamp and a more contemporary adversary, Lisa Simpson. This exhibition brings Sachs’s reinterpretations of Picasso, Duchamp and Simpson’s works into conversation to create a wry reflection on the purpose of painting.

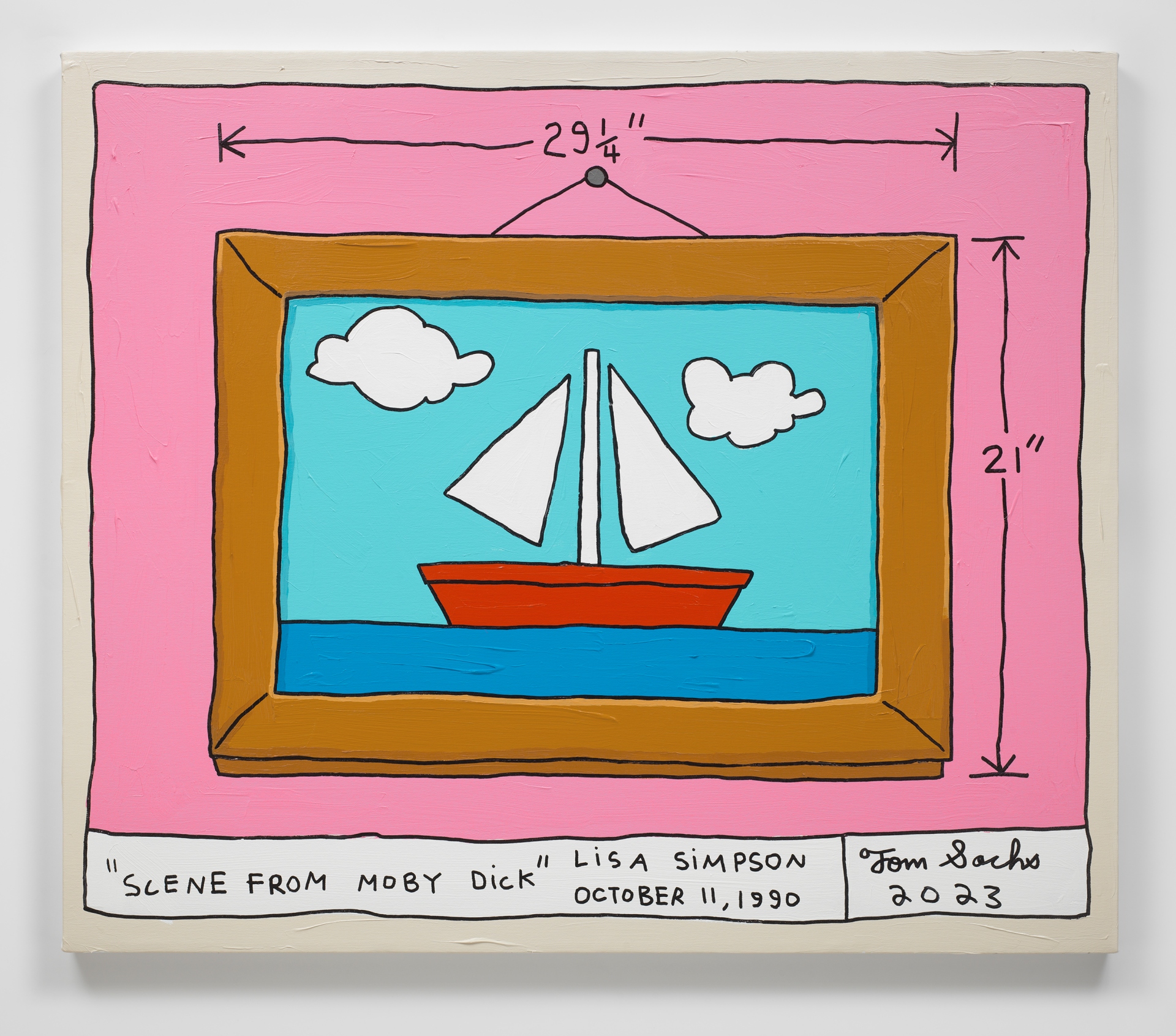

Scenes from Moby Dick, 2023

Acrylic and krink on canvas

91,4 x 106,7 x 3,8 cm (36 x 42 x 1,5 in)

(TSA 1470)

Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul © Tom Sachs. Photos: Studio Tom Sachs

Painting is a medium Sachs has returned to several times over the years, and the works on view were conceptualised in a period of focus on drawing and colour for the artist. In his New York studio, he surrounded himself with the work of some of the masters of Modern art: Picasso and Duchamp, two giants of the 20th century. The Modernist painter and the boundary-pushing ironist are often positioned in opposition to one another, and their different approaches to what makes a work of art – both of which Sachs identifies with in different ways – prompted Sachs to bring the two head-to-head in “Painting”.

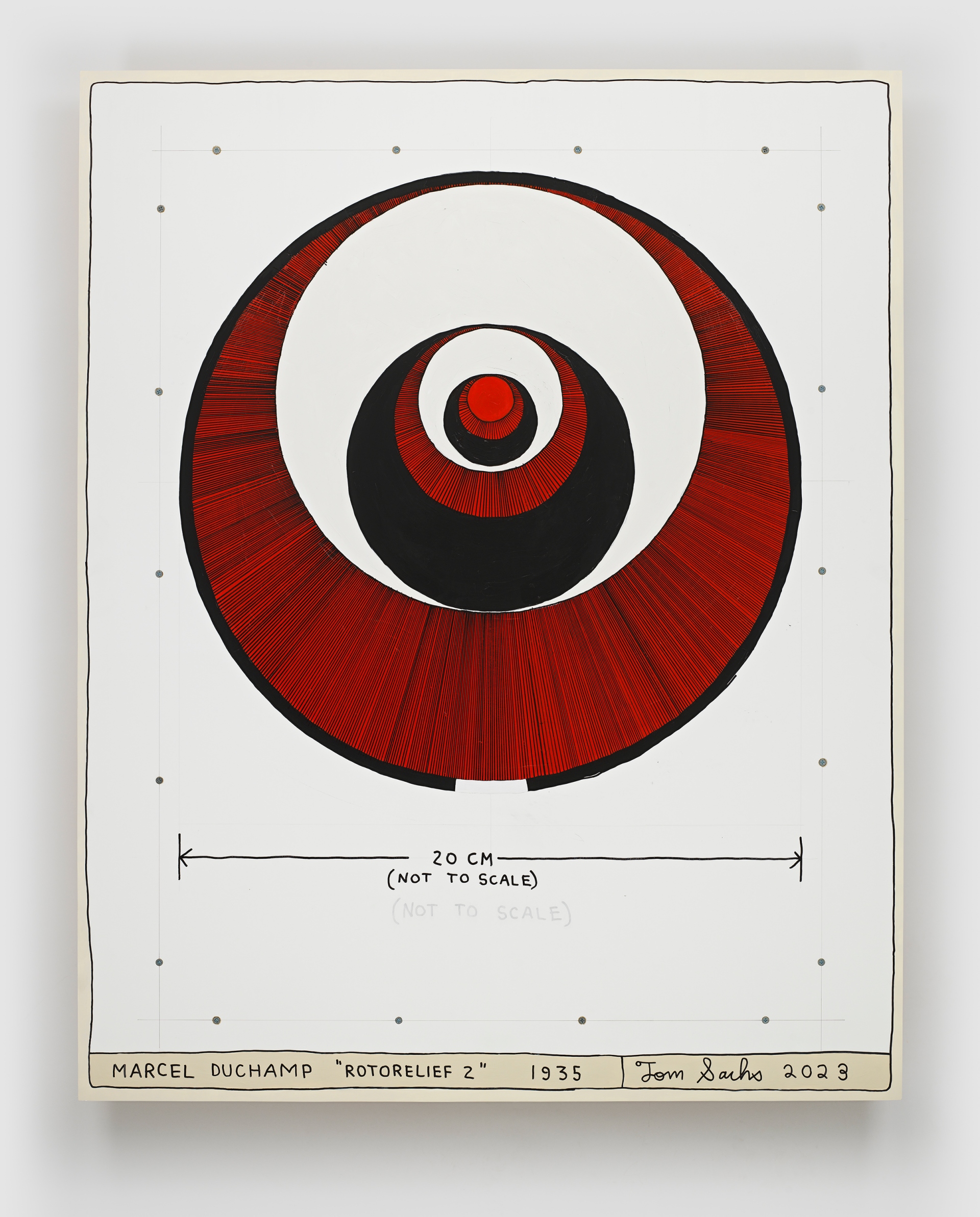

Rotorelief, 2023

Acrylic, Krink, and harware on panel 152,4 x 121,9 cm (60 x 48 in)

(TSA 1477)

Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul © Tom Sachs. Photos: Studio Tom Sachs

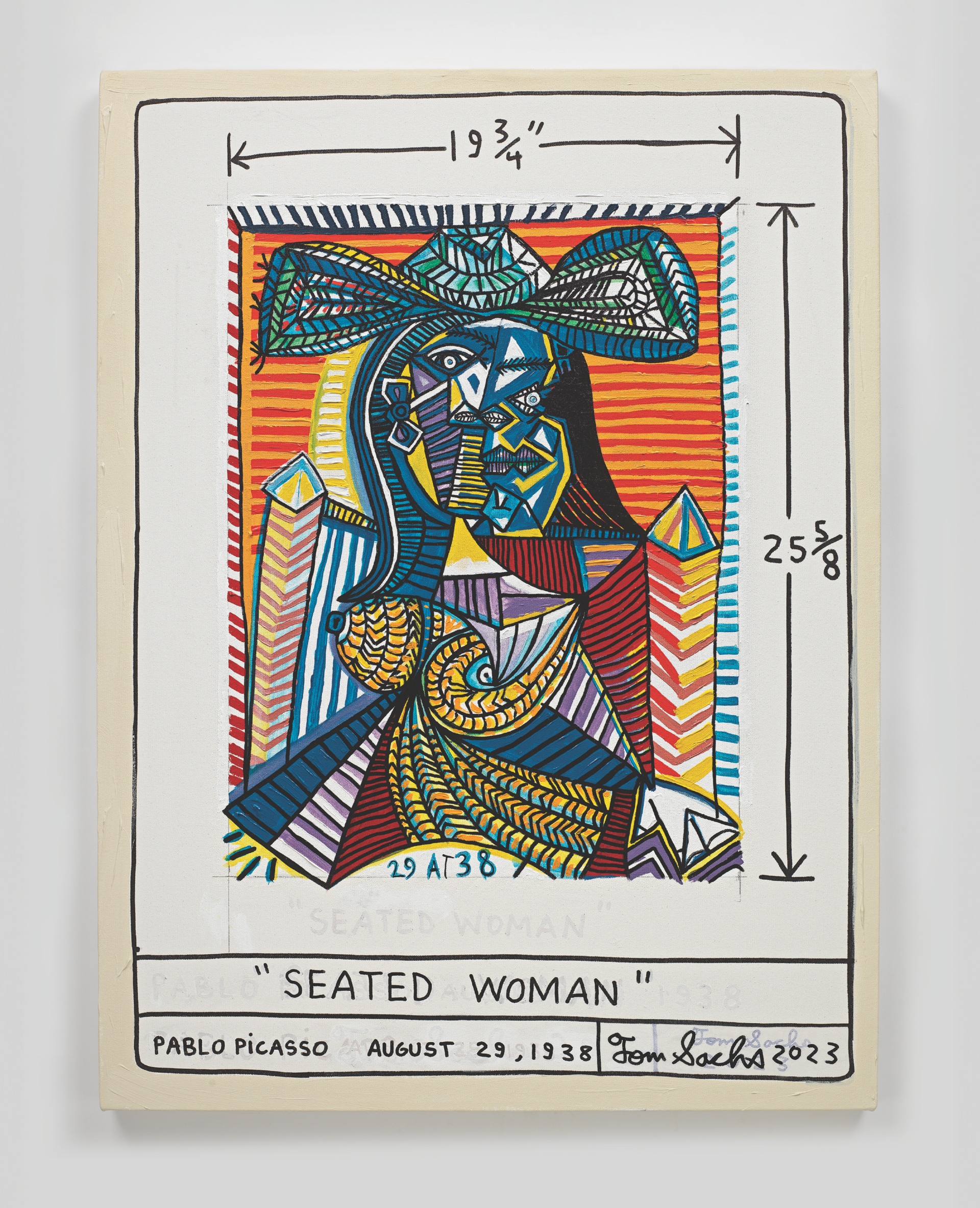

Exploring the lines and forms used by Picasso in the Spanish painter’s lesser-known works created starting in 1937, Sachs found parallels with his own practice. The thick lines that recur in Sachs’s work, originating from the influence of American graffiti and street art, mimic the solid black linework that delineates many of Picasso’s figures. Sachs’s choice of the works he would reimagine for the exhibition reflects many of the notions he discovered in Picasso’s works that vibrantly resonated in a contemporary context.

Seated Woman, 2023

Synthetic polymer and Krink on canvas 101,6 x 76,2 x 3,8 cm (40 x 30 x 1,5 in)

(TSA 1478)

Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul © Tom Sachs. Photos: Studio Tom Sachs

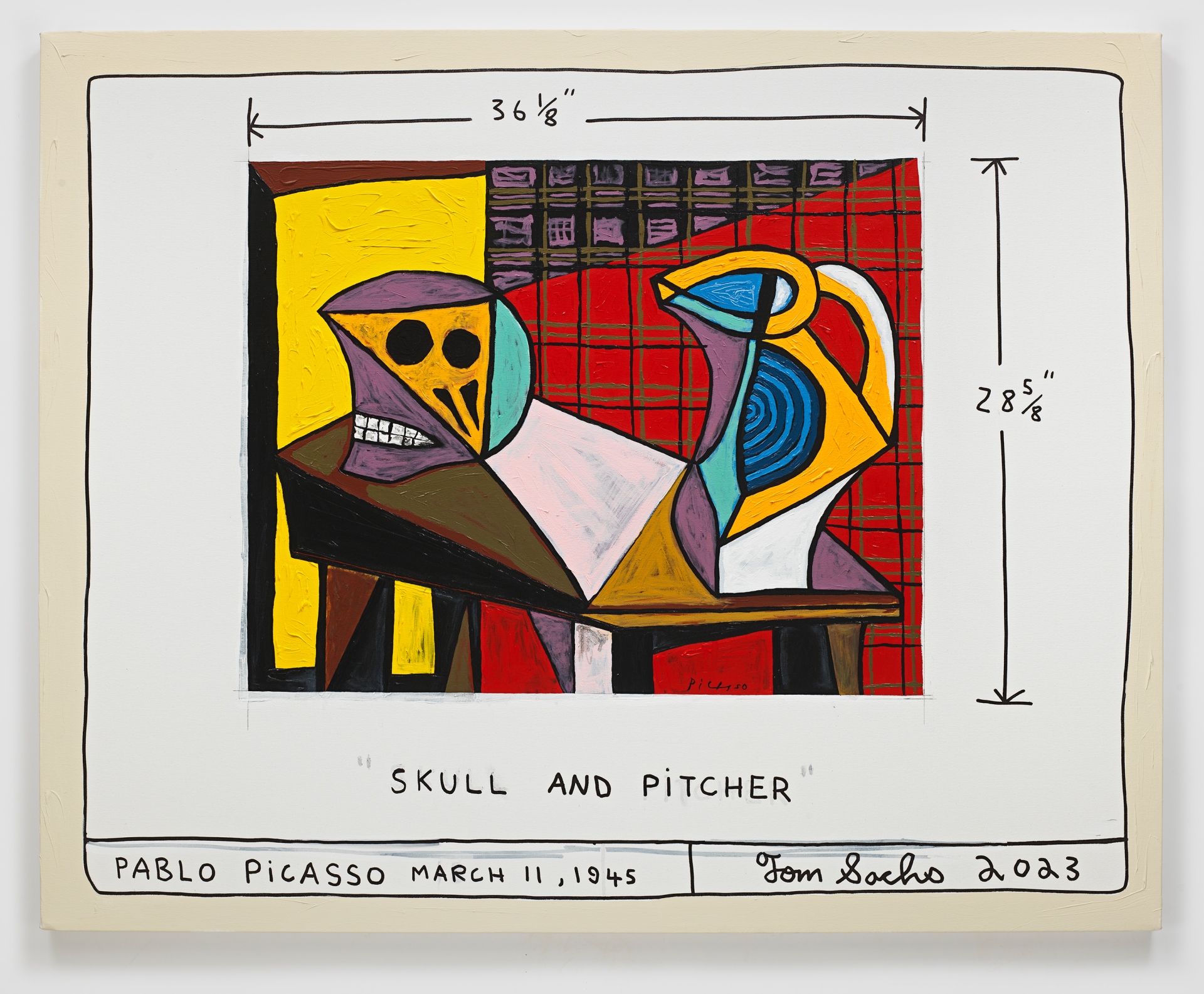

The horrors of war and the reality of mortality weighed heavily on Picasso. As such, the still lifes in the exhibition are devoid of softer memento mori – fruit or flowers, for example – and are instead centred around human skulls, the heads of beasts, and the barbed forms of sea urchins. In contrasting complement to this sentimental approach, Picasso’s playful and touching scenes of childhood – often depicting children from his own family and from his entourage – seem to connect movement and life with the hope of a new generation.

Still Life with Skull and Pitcher, 2023

Synthetic polymer and Krink on canvas

121,9 x 152,4 x 3,8 cm (48 x 60 x 1,5 in)

(TSA 1472)

Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul © Tom Sachs. Photos: Studio Tom Sachs

Sachs’s affinity with aspects of Picasso’s work is intriguingly disrupted by the critical eye Sachs has long cast at traditional methods of artmaking used by artists such as Picasso, as Sachs, like Duchamp, invites viewers to see everyday objects as sculpture. In the midst of the journey through Picasso’s work with its meandering lines and blended colours, Duchamp’s bold black, red and white Rotorelief introduces the viewer to the rivalry between the two leaders of Modern art. While Picasso’s works are recreated at their original scale, Sachs’s reimagination of Duchamp’s Rotorelief dramatically expands it to 10 times its initial size. With its imposing new scale, strength of colour and sharp lines, the single Duchamp piece finds its voice among the Picassos that surround it, encouraging the viewer to engage with the challenge that it poses to more traditional conceptions of what constitutes a work of art.

When Duchamp debuted his Rotoreliefs in 1935, at 20 centimetres in diameter, the discs were a commercial object – exhibited at a fair for inventors, they were marketed as optical illusions rather than paintings to be hung on a wall. Sachs’s longstanding interest in mass production, industrialisation and commercialism, and his exploration of and playful engagement with these themes in his own practice, would have placed him firmly in Duchamp’s camp, rather than in Picasso’s. As such, through his reworking of Rotorelief for the exhibition, Sachs’s fascination with the place of consumerism in art provides a counterpoint to the purist approach represented by Picasso.

Women were frequently included in Picasso’s paintings, often through the lens of their relationships with him and as symbols bearing the world’s pain. Sachs’s unexpected inclusion of his version of a work by ‘Lisa Simpson’, a character from the animated television series The Simpsons – a ‘painter’ who is both female and fictional – is a direct challenge to Picasso’s approach. Echoing a key tenet of Sachs’s own work, finding a place for humour, irony and play in artmaking, the character, who has no formal training, paints for pleasure and has no personal relationship to Picasso, is the ultimate rival that Picasso could not have anticipated. Her painting, which hangs over the iconic Simpsons sofa – and which Sachs ventures might well be ‘the most seen painting in the world’ – makes Lisa a formidable opponent. By placing a Lisa Simpson work in dialogue with his recreations of Picasso’s and Duchamp’s, Sachs suggests a fresh alternative to established perspectives on what art is for. In introducing Picasso to Lisa Simpson, Tom Sachs completes his ultimate Duchampian gesture.