Born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa, William Kentridge grew up under the destructive pall of apartheid. As the son of human rights lawyers, he developed a strong sense of social responsibility from an early age. In 1978, Kentridge earned a Bachelor’s degree in Politics and African Studies from the University of the Witwatersrand, as well as a diploma in Fine Arts from the Johannesburg Art Foundation where he studied under the influential South African artist Bill Ainslie. In the hopes of becoming an actor, Kentridge went on to study mime and theatre at L’Ecole Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris in 1981.

In his formative years in the 1970s and 80s, Kentridge worked as a writer, director, set designer, puppeteer, and actor. By the time he was thirty years old, Kentridge began to combine his theatrical ambitions with a renewed interest in his drawing practice. Gravitating toward charcoal, a medium that with a wipe of a cloth can change a drawing as quickly as one can think, he found he could work in a flowing free association style that could undergo constant redefinition and change.

Inspired by the process of how a drawing comes into being, Kentridge began to produce stop-action films of himself creating these animations in a Neo-Expressionist and German cinema influenced style. These filmed drawings, or drawn films, dwell in a state of pause between stillness and movement. Working without a script or storyboard, Kentridge is open to recognizing his subjects as they naturally occur and come to be, demonstrating how we make sense of the world. Many of these filmed drawings are deeply influenced by his homeland’s socio-political landscape. Between 1989 and 2020, Kentridge has continually added to a series of short films titled ‘Drawings for Projection’ that follow the lives of mining tycoon Soho Eckstein, his wife, and her lover Felix Teitlebaum, as they deal with the effects of the final decade of apartheid.

Says Kentridge, “I’m interested in the weight of history on us.” In work created over the past five decades, this intellectual artist has parsed and questioned the historical record – responding to the past as it ineluctably shapes our present – and in doing so, has created a world that mirrors and shadows our own. Through film, performance, theatre, drawing, sculpture, painting, and printmaking, Kentridge seeks to make sense of the world and the construction of meaning; his work brings viewers into awareness of how they see the world and navigate their way to more conscious seeing and knowing.

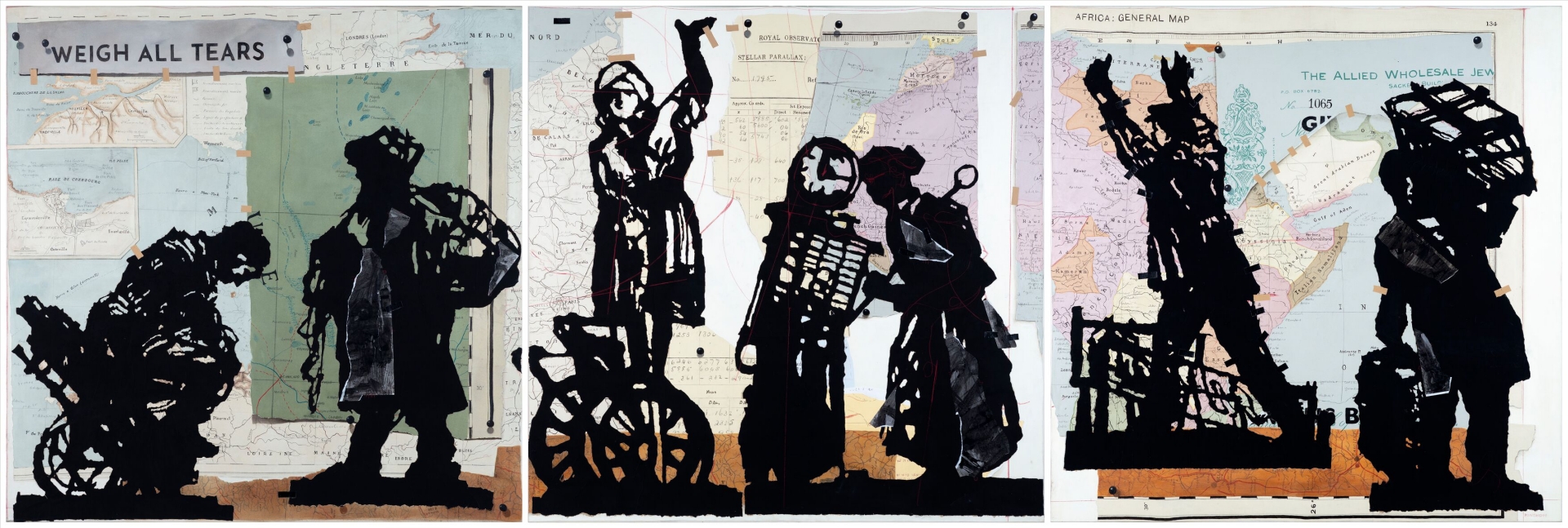

Opening 17 March, Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong will present ‘William Kentridge. Weigh All Tears’, an exhibition organized working closely with Goodman Gallery. This is Kentridge’s first solo exhibition in Hong Kong, and the first project between Hauser & Wirth and this Johannesburg-based artist. The exhibition takes its title from a new 6-metre-wide triptych of the same name, where silhouetted figures form a procession against a collage of maps of Africa and archival documents. ‘Weigh All Tears’ is a phrase that cycles through Kentridge’s work, one of an evolving miscellany of phrases that recur in his work. They are ‘unsolved riddles, phrases which hover at the edge of making sense.... fragments of sentences which sit in a drawer of phrases used in other work over the years. On occasion they get taken out and sorted through.’

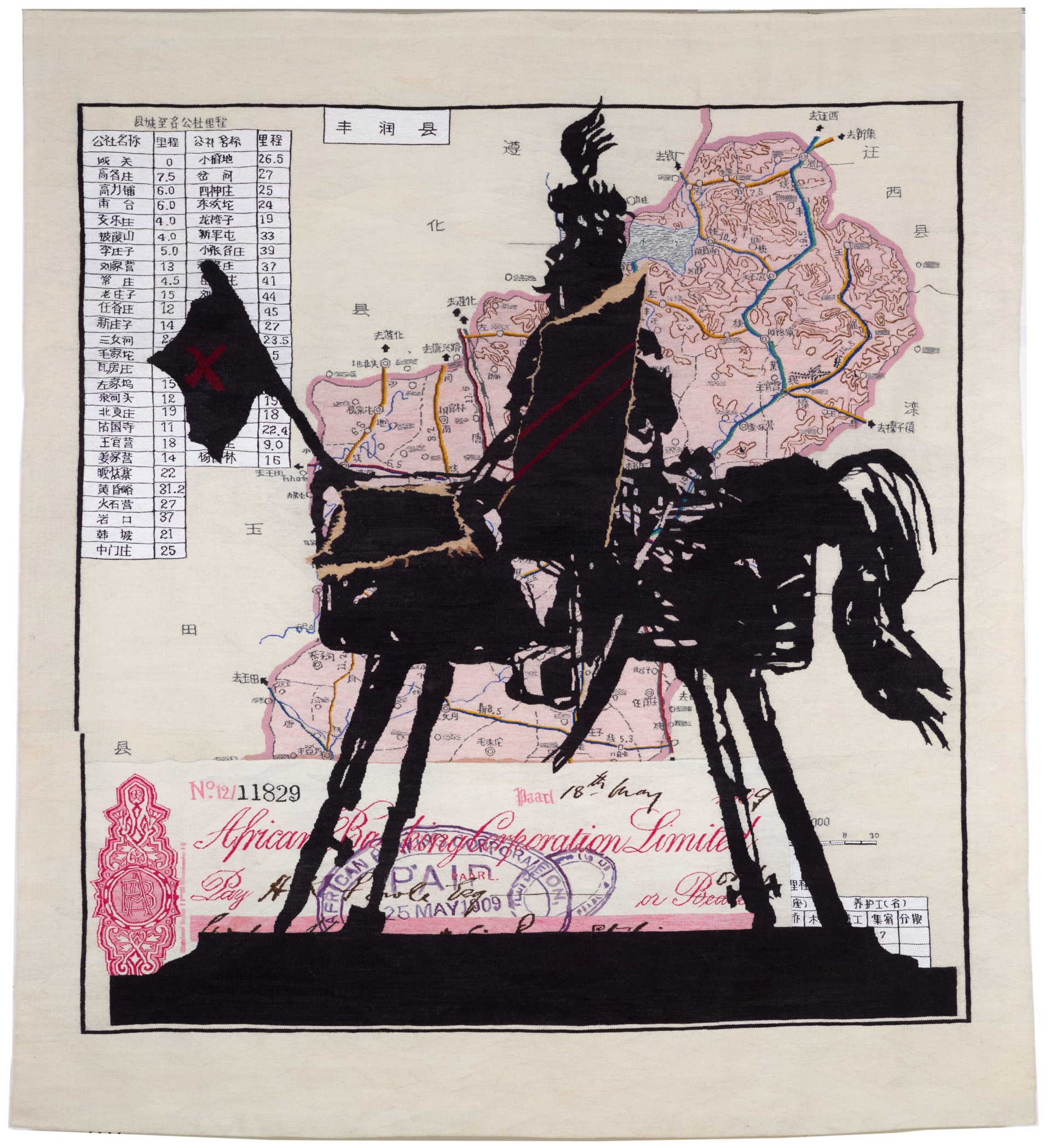

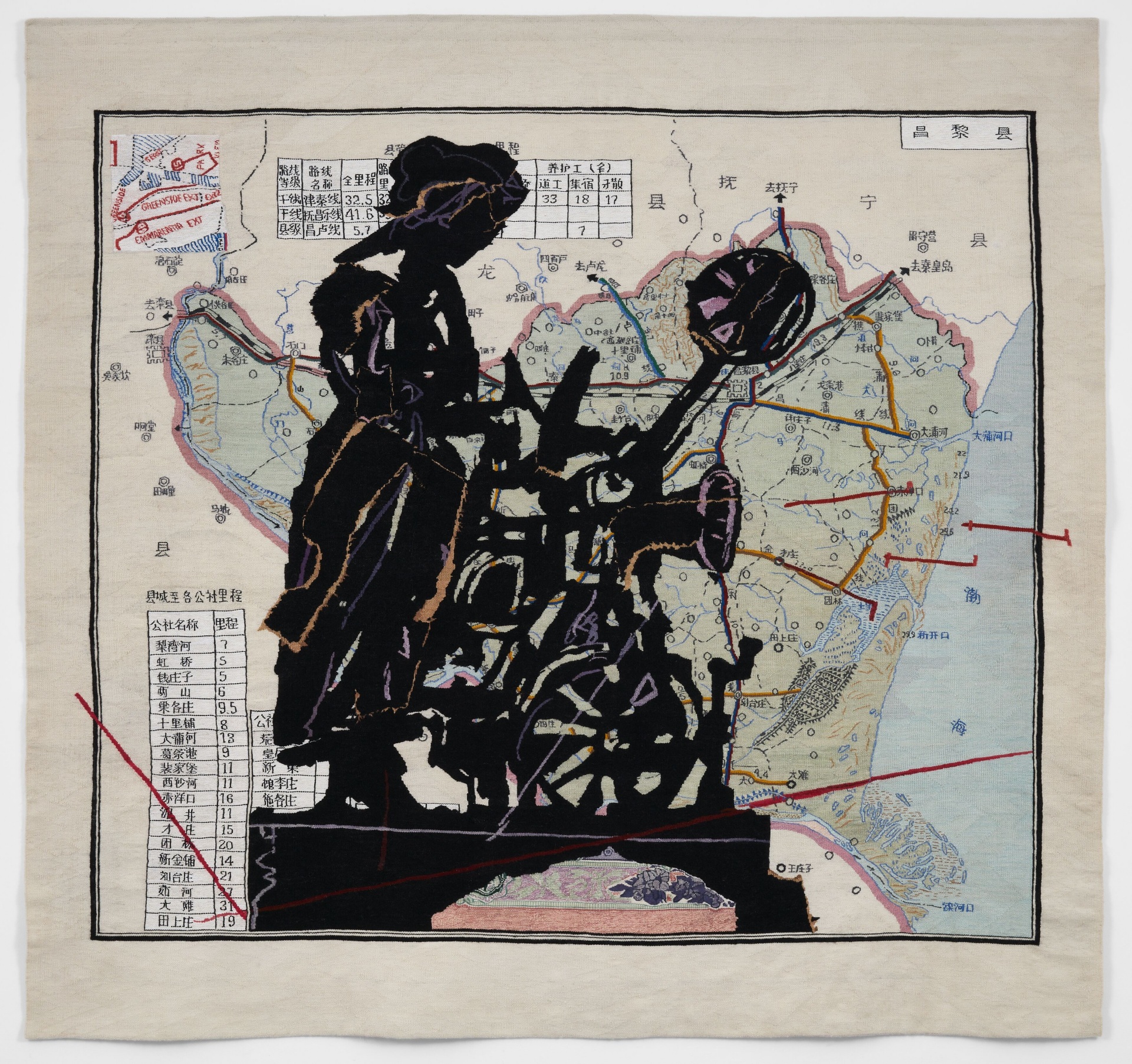

The figures in the triptych, like the phrases across different works, can be seen in four new tapestries in the exhibition: ‘Orator’ (2021), ‘Spinner’ (2021), ‘Mechanic’ (2020), and ‘Colleoni’ (2020). Since 2001, Kentridge has collaborated with Marguerite Stephens and her weaving studio outside Johannesburg, to translate the artist’s designs into hand-woven mohair tapestries. In the current series of tapestries, laser-cut silhouettes stand against backdrops of a Chinese political roadmap of the Hebei Province (ca. 1950-1970). The artist bought the Chinese maps seen here 20 years ago, waiting for the right moment and conjunction of images to present themselves, inviting their use. The tapestries create a space of multiple times and places, a space of inquiry and doubt: the era of the 1950s-1970s Chinese county map and the outlined figures, sometimes overlaid with colored marks and vestiges of collage technique.

The figure in the tapestry ‘Colleoni’ (2020), Bartolomeo Colleoni, was a mercenary and Captain General of Venice in the 1400s, depicted in a similar way as the Qianlong Emperor was painted by the Italian artist Castiglione in the 1700s. The figure on horseback recurs in Kentridge’s work, materializing his reflection on the heroics of men made resplendent by putting them on horses and elevating the horses on pedestals; and the subsequent disintegration, decay or destruction of those monumental figures. Here the horse is constructed from disparate elements and throws the heroic nature of such figures in question. Through bricolage of wooden elements (including ladder legs), ‘Ladder Horse’ (2021) explores reduction of form and presents us with another horse of doubtful heroism. Similarly, the three laser cut steel heads, ‘Revolutionary I’, ‘Revolutionary II’ and ‘Revolutionary (There Was No Epiphany)’ (all 2016) show a progressive ideogramic progression of a head taken from a model opera poster, with the last iteration incorporating text. The model operas of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) reworked the form of the Peking operas with revolutionary stories.

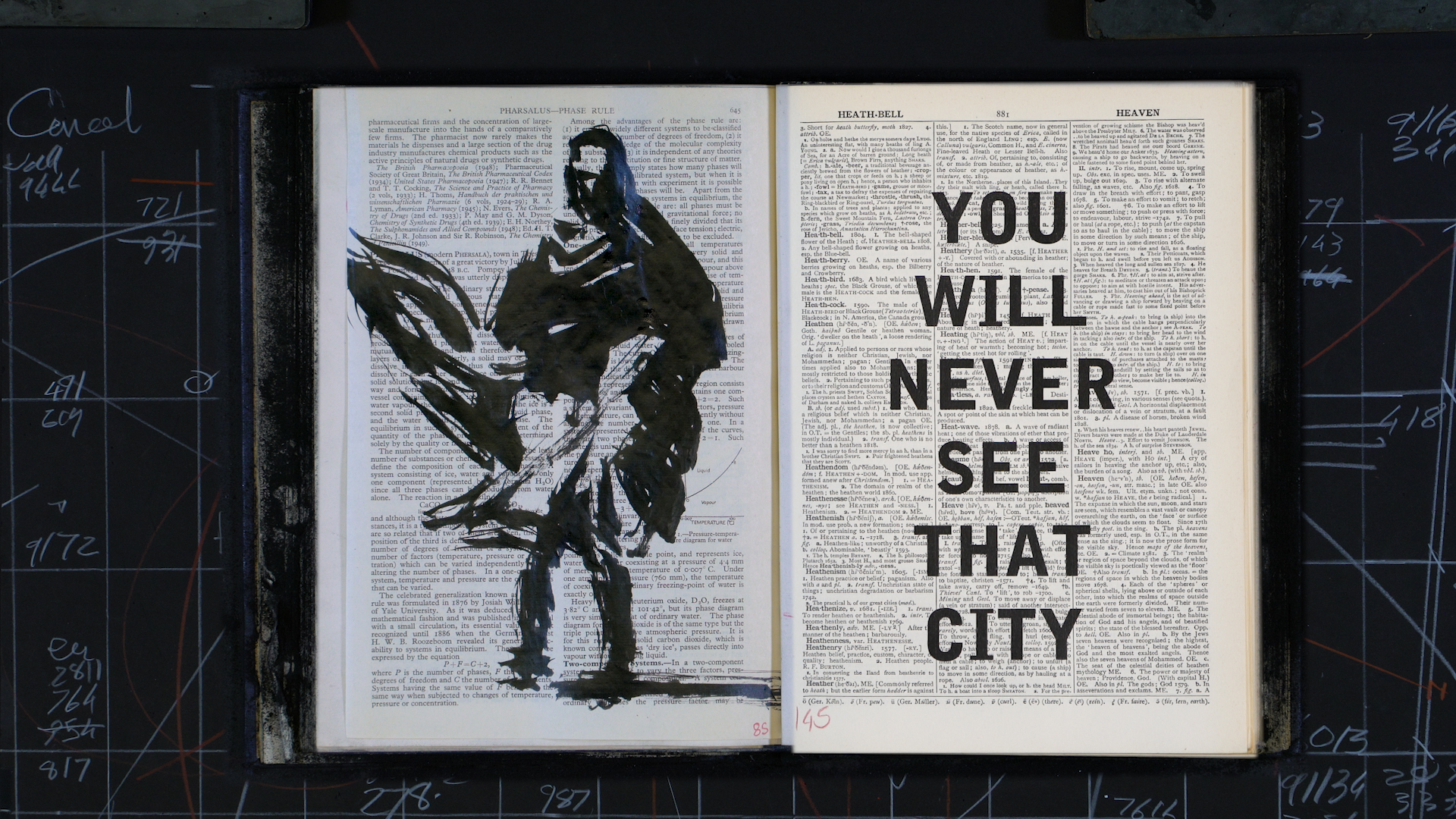

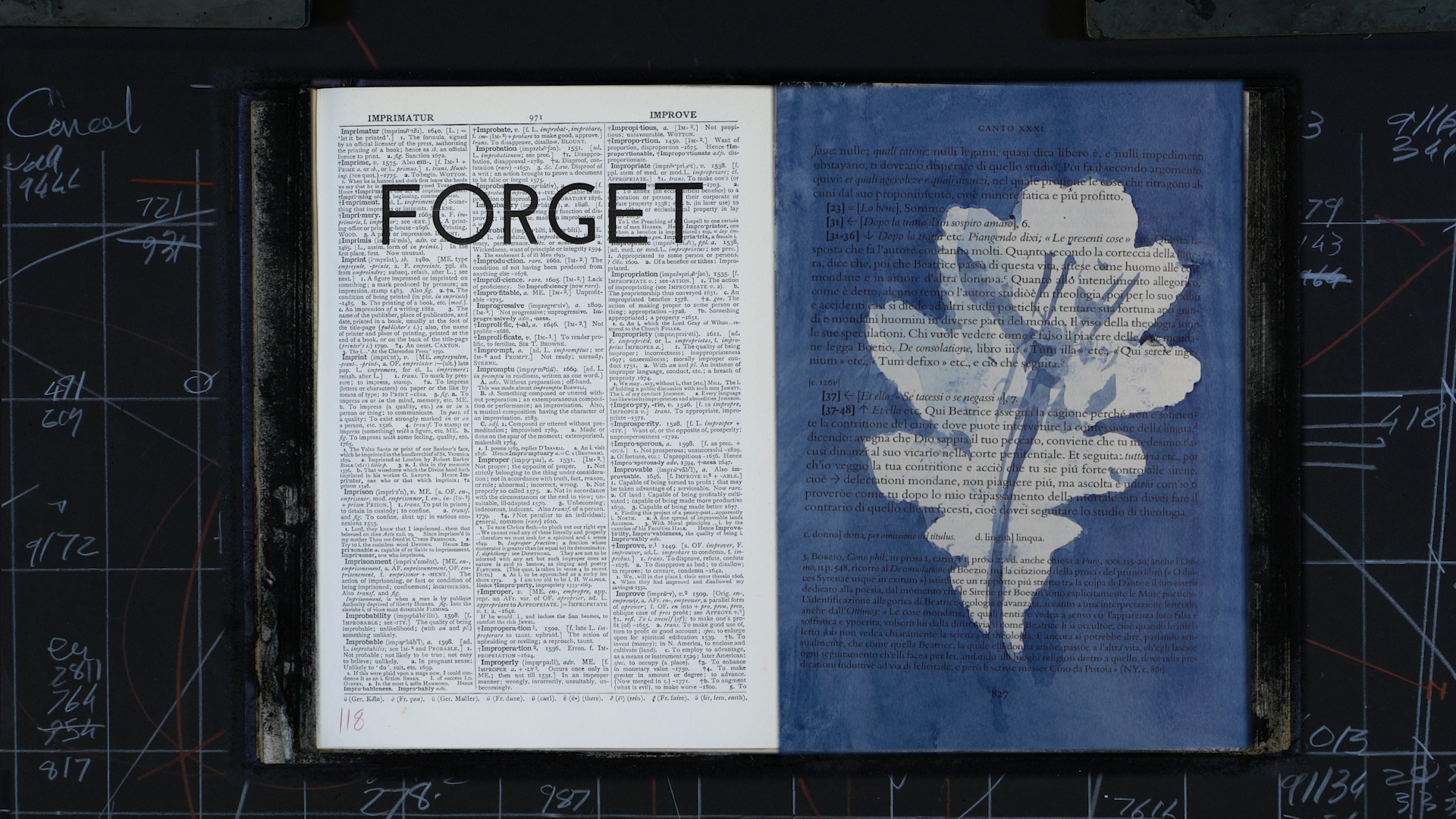

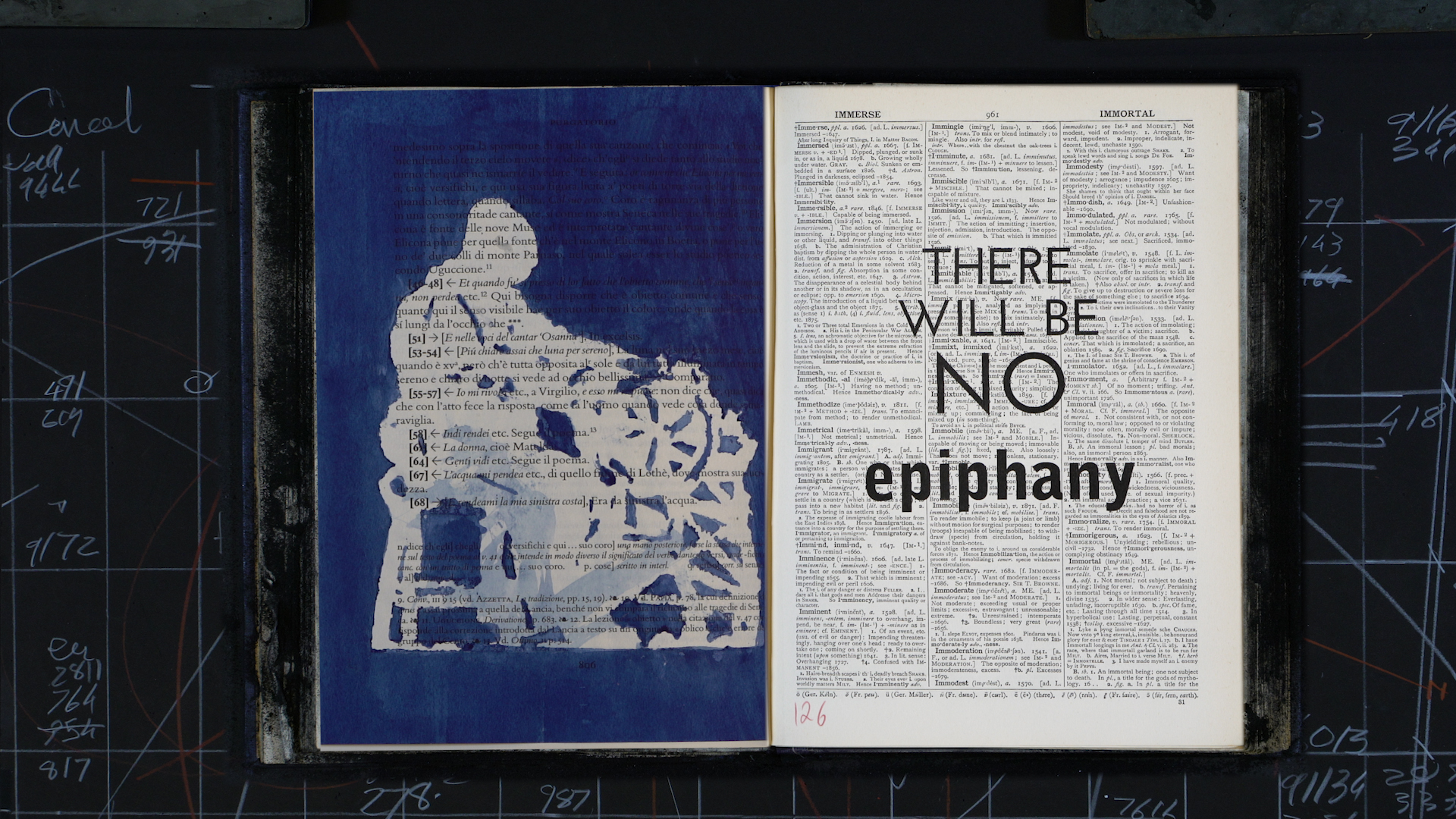

Also on view in the exhibition are a series of bronzes made in 2021 and cast at Workhorse Foundry in Johannesburg. A number of the sculptures are larger iterations of figures from the series of 40 small bronzes titled ‘Cursive’ (2020). Collectively the glyphs begin to read as a three-dimensional lexicon for the artist’s practice. The images started as a series of ink drawings and paper cut-outs on single dictionary pages. Kentridge experimented with the visual language of glyphs and symbols transformed into sculpture, then played with their arrangement on shelves and in procession. Arranged in different sequences, the works read differently. A group of seven bronzes at larger scale is one configuration of possible meanings and associations. For Kentridge the glyph bronzes and the connections between them could be seen as a kind of self-portrait. ‘As if one definition of ourselves is the mass of associations with which we are filled, all of them waiting to latch onto the world and its objects as they come towards us.’

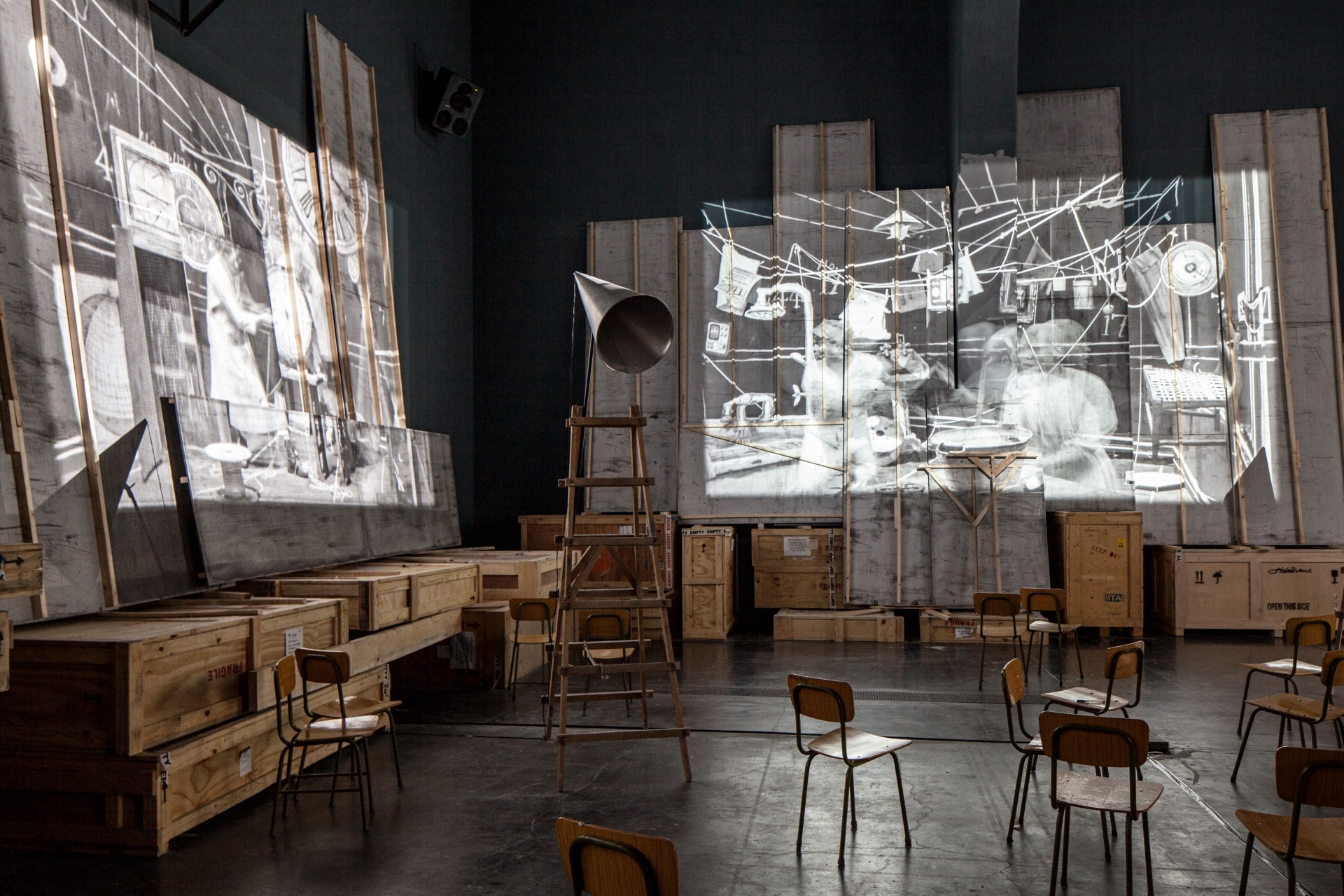

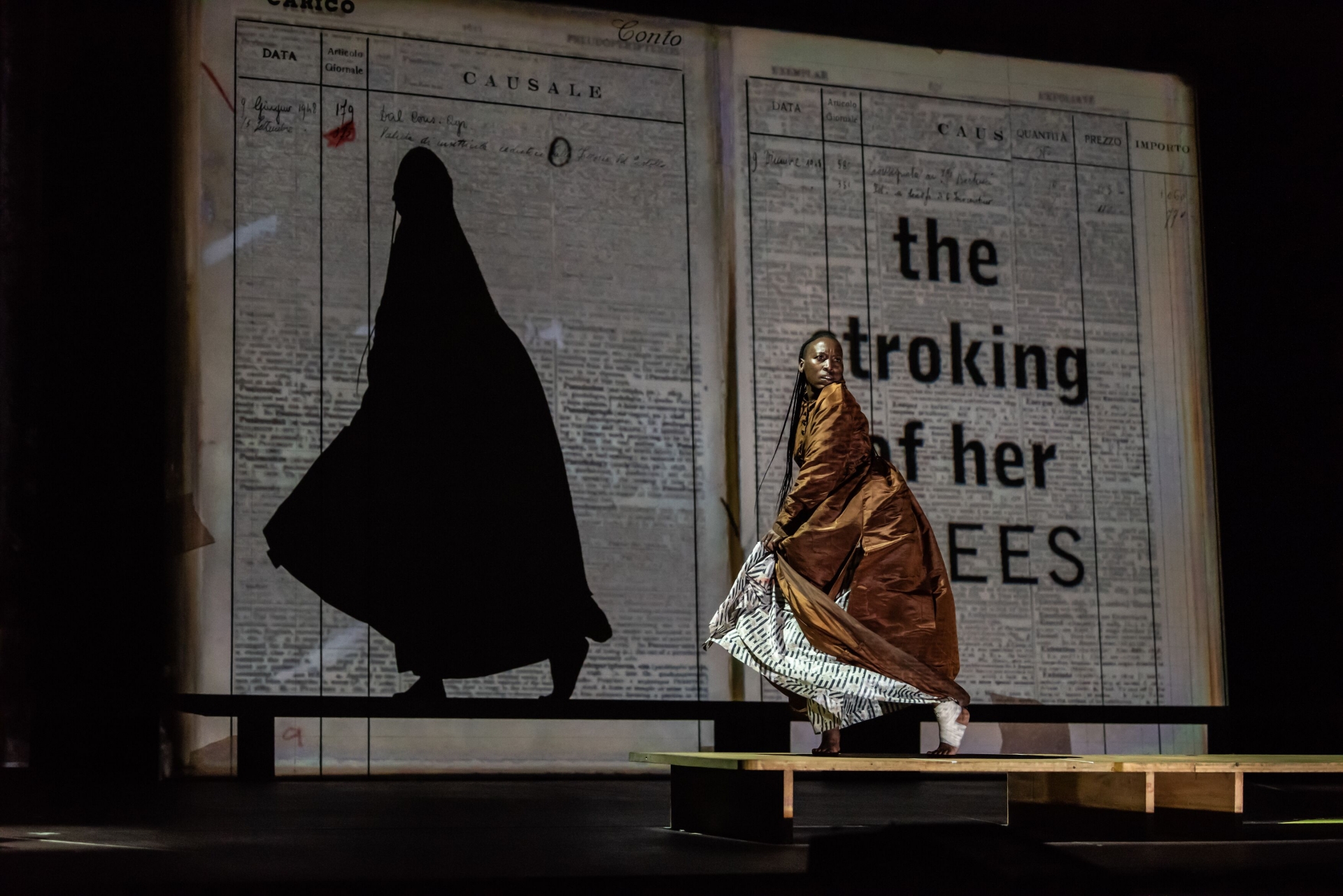

Finally, the 2020 film ‘Sibyl’ – which arises out of his 2019 opera ‘Waiting for the Sibyl’, commissioned by the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma and made in collaboration with composers Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd – brings together many of the figures, symbols and phrases found within the exhibition, which are seen within the flickering flipbook to a haunting soundtrack. The worker figures reappear in cyanotype blue paint. Drawn leaves appear along with drawings of trees, the figure of the dancing Sibyl, pages of effaced text, household objects, and abstract shapes. The text of the film is taken from the libretto of the opera, which gathered lines from poets, renderings of African proverbs, and lines written specifically for the opera. ‘Day will break more than once’; ‘All so different from what you expected’; ‘Where shall we put our hope?’; ‘You will never see that city’ are among phrases which appear, only to vanish.

Inspired by the myth of the Cumaean Sibyl – who would answer people’s questions about their destiny on oak leaves, which, however, inevitably blew in the wind and became confused – the film and its turning pages and transforming images are a reflection on fate and mortality. Kentridge has said, “Hovering over the piece is the awareness that our contemporary Sibyl is the algorithm, which knows us and our destinies better than we do.”